Eminem lyrics are often discussed for their poetic merit, but fewer people mention how Eminem’s personas connect with those of modernist poetry.

Anyone familiar with Romantic poetry will know what strong personas the Romantic poets had. Lord Byron, John Keats, William Blake, William Wordsworth all wrote in a way that meant you could almost tell who wrote them, though clearly their poems’ speakers differ from the poets’ actual characters and personalities.

Romantic poets often depicted the poet as a hero or the poet as a prophetic, bringing spirituality, divinity, and the sublime in the aftermath of the Enlightenment’s science and logic.

The Modernist Persona

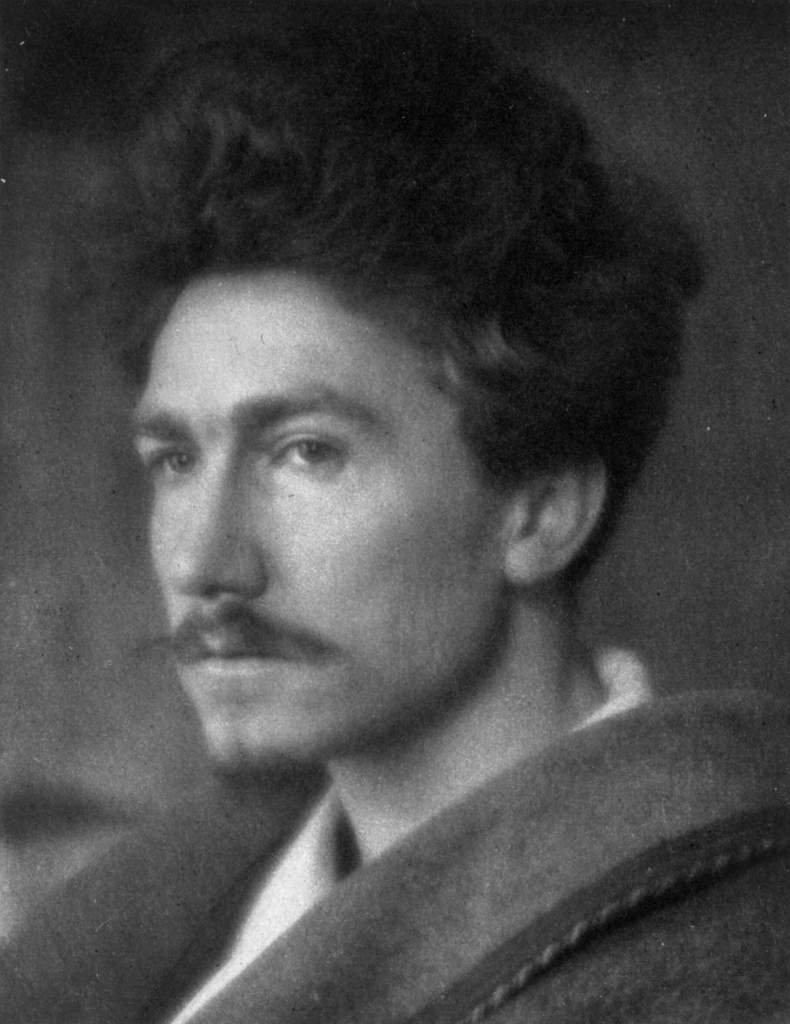

During the modernist era, however, poets started to take on different personas depending on the work. The persona of the speaker in T. S. Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock is similar to that of T. S. Eliot but also a lot different.

In The Waste Land, there are many speakers, and it’s unclear whether one speaker takes on different personas or whether these are actually different speakers. Each one of these personas differs, yet the poems were all written by the same prolific poet, T. S. Eliot.

Indeed, in modernism, there was actually a clear persona: the persona of having many personas.

Eminem’s Personas

When people discuss the legitimacy and reputation of rap music as an artistic genre, you’ll often hear the words “Eminem” and “poetry.” I’d say that it’s so common that it’s becoming somewhat of a cliche, so let me add my say! No modern poetry blog could surely be complete without the mention of Eminem, right?

The English author, Giles Foden, wrote in The Guardian about why he believes Eminem is a poet. Scott F. Parker dedicated an entire book, Eminem and Rap, Poetry, Race: Essays, that contains the topic of poetry, rap, and Eminem.

If that’s not enough for you, the Nobel Prize-winning poet and former professor of poetry at Oxford University, Seamus Heaney, praised Eminem’s lyrics. According to The Independent, The Poetry Society of London, formed in 1909, said it wasn’t surprised by Heaney’s remarks, adding that: “Eminem harnesses the power of word and language and that’s what a poet would do.”

A lesser known topic is that of Eminem’s personas. In the Fall 2019 edition of the Culture, Society and Masculinities academic journal, Anna Hickey-Moody labelled these personas as: “The Everyman, the Needy Man, the Hegemon.” She added that:

Eminem’s White/Black persona can be seen as interchanged with two lyrical alters-Marshall Mathers the everyman character and Slim Shady, the psychiatrically unwell and needy young man.

Anna Hickey-Moody, Eminem’s Lyrical Personae: The Everyman, the Needy Man, the Hegemon, Culture, Society and Masculinities, 2009

In 2002, Time magazine’s Josh Tyrangiel also described Eminem’s personas, as “The Three Faces of Eminem.” Eminem’s The Slim Shady LP and The Marshall Mathers LP created much controversy due to their explicit and violent nature, as well as their homophobia. He claimed that he was simply being an artist.

He was a guy named Marshall Mathers with a rap alter ego named Eminem, and that alter ego happened to have a lunatic doppelganger of its own named Slim Shady. He was merely playing a role (or three).

Josh Tyrangiel, The Three Faces Of Eminem, TIME, May 26, 2002

From my perspective, we can also break down Eminem’s persona’s like this:

Marshall Bruce Mathers III – That is the real man, and that is his legal name. This persona also features in some of Eminem’s music, as the lyrics are based on Mathers’s life. This persona is more humble, honest, and personal than the others.

One example is his famous 2002 song, Lose Yourself, from the movie 8 Mile. He won the 2003 Academy Award for Best Original Song wit this song:

Eminem – If you look at Mathers’ initials, you may notice something familiar: M and M, or Eminem. This persona is just a rapper, one that likens himself to a Rap God as in this 2013 song, clearly much less humble than the Mathers persona:

Slim Shady – This persona is the playful, naughty, dirty-minded one. He is more aggressive and offensive than the other two personas, bordering on the sociopathic. However, like Mather, he is at least brutally honest, saying in his 2002 song Without Me:

Though I’m not the first king of controversy

Source: LyricFind

I am the worst thing since Elvis Presley

To do black music so selfishly

And use it to get myself wealthy

Songwriters: Anne Jennifer Dudley / Jeffrey Irwin Bass / Kevin Dean Bell / Malcolm Robert Andrew McLaren / Marshall B Mathers / Trevor Charles Horn

Without Me lyrics © Peermusic Publishing, Kobalt Music Publishing Ltd., BMG Rights Management, Reach Music Publishing

In the modern world, rhyme can often sound childish or funny, but those lyrics seem to do both. Yet they’re also honest, and I’m pretty sure a lot of people find them offensive.

Just like modernist poets created the trend of the persona of having many personas, Eminem takes on different characters depending on the tone of his lyrics and music.

In that sense, perhaps Eminem’s lyrics and personas work like T. S. Eliot’s objective correlative, “a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion.”

Poetry Foundation says: “There must be a positive connection between the emotion the poet is trying to express and the object, image, or situation in the poem that helps to convey that emotion to the reader.”

Clearly, the lyrics and music of Eminem’s different songs match his personas and the mood they intend to convey. In fact, scroll up and look at the thumbnails for each song, and you’ll immediately see these differences.

Also, let’s not forget that he also took on another persona as an actor in 8 Mile, but that’s expected. Then again, a musician having different personas when lyrics are a form of writing or a sort of poetry, should be expected too.

What About Our Personas?

We may see different personas in poets like Eliot and musicians like Eminem, but we all use personas all of the time, whether we’re famous or not. Oxford’s Lexico Dictionary defines persona in two ways:

– The aspect of someone’s character that is presented to or perceived by others.

– A role or character adopted by an author or an actor.

Persona, Oxford’s Lexico Dictionary

We behave one way among family members and even within our families we behave differently with our siblings and cousins than we do without grandparents. We behave another way with our friends and a different way with colleagues and another with acquaintances and people we barely know or don’t know at all like store workers.

And let’s not forget how our social media and other online personas differ much more than our real life ones. For example, when people from university add me on Facebook or Instagram, I often don’t recognize them because of the edits they’ve made to their profile photos.

So the next time someone says, “Be yourself,” you could say you’d rather, “Lose yourself,” or you could ask them, “Which yourself should I be?” Just like the persona of having many personas, your individualism is composed by the many individuals that make up who you are and how you act. And you already do that whether you realize it or not.