Marriage

So different, this man

And this woman:

A stream flowing

In a field.

William Carlos Williams – Marriage

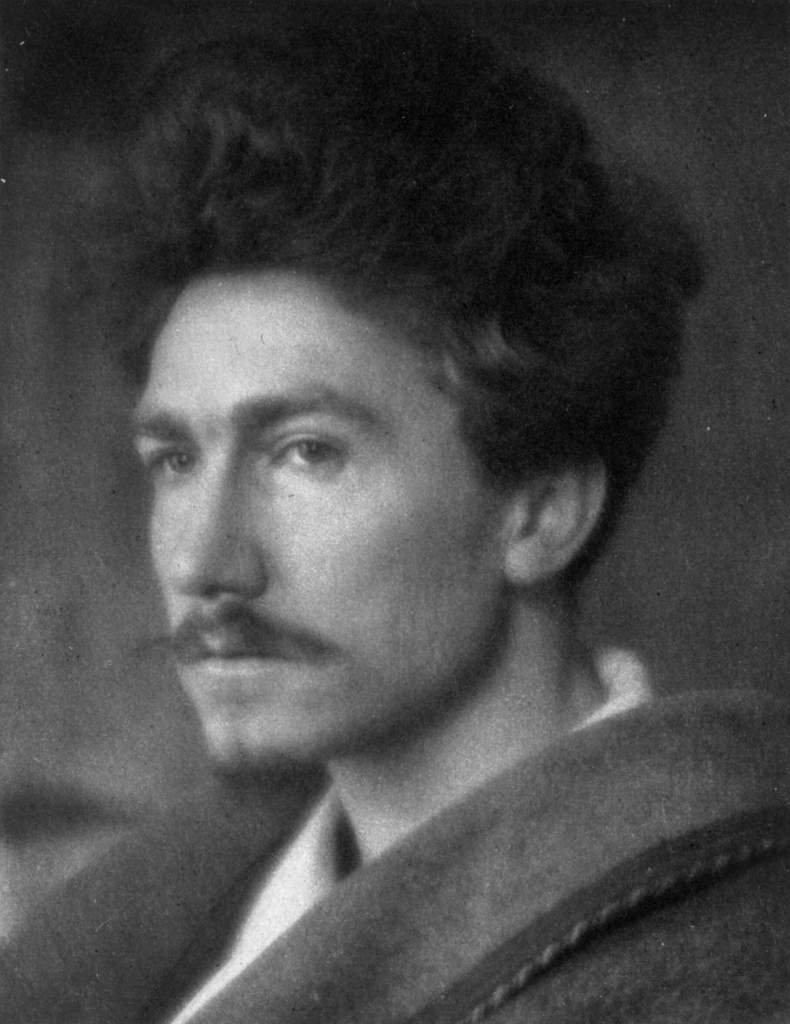

This early 20th-century imagist poem by Puerto Rican American poet, William Carlos Williams, explains marriage in such a simplistic but magical way. I’ve written about marriage and love in modernist poetry before here, namely Ezra Pound’s translation poem, The River-Merchant’s Wife: A Letter. Pound’s poem was not imagist, but it did reveal a deeply personal and intimate side of a wife’s love for her husband. But Williams’ poem does not mention emotions, and it’s only 14 words long. Yet it evokes strong sentiments in me, just like imagist poets intended.

Imagist poetry aspires to depict a specific moment in time in an exact location while still being universal enough to evoke a strong response in the reader. Imagism also emphasizes using the minimum number of words necessary to create meaning and elicit the reader’s emotions and intellect.

Pound described the masses of people in a metro station so succinctly in another imagist poem, In a Station of the Metro which I explained here. That poem is also 14 words like Williams’ Marriage. For comparison, Shakespeare’s famous Sonnet 18, “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” contains 114 words, one hundred more than Pound’s and William’s poems. I felt a strong sense of individuality and confusion in a metro station a few weeks ago when I realized what Pound meant in saying “these faces” merge together in an almost ghost-like manner.

William’s Marriage seems like an eternal yet ephemeral moment. It’s eternal because it could apply to any marriage anywhere on earth at anytime, past, present, or future to any man and woman. But it’s ephemeral because so much could happen after the moment ends. And in fact, there isn’t really a sense of time in this poem. Are the two individuals getting married? Are they already married? Were they once married? None of it is clear. This poem is really meant to be perceived by the reader, and our interpretation of it could differ.

To me, the key in understanding this poem lies in “A stream flowing / In a field.” Is the stream supplying fresh water to the field? Why does the field surround the stream? What is the field? These questions don’t really matter to me.

When I first read Marriage I thought about how a stream often merges into a river, just as two people become one in a marriage. They’re somehow individuals as part of the stream but become one united stream on the river of life. That river eventually becomes an estuary, feeding the sea. So, the stream symbolizes the path this couple might take before they eventually die and become one with nature again in the sea, a mass of souls no longer suffering life’s struggles.

Streams represent water, a life-giving substance. Marriages give birth to children. Okay, around the time this poem was written in the first half of the 20th century, childbirth was mostly through marriage. In 2018, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) says that, “On average across OECD countries, 40% of births occur outside of marriage.”

According to the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, only about 40% of 2017 births in the U.S. occurred outside of marriage. So even today, marriage is the most common way children are born. See Williams’ universality and near-timelessness yet?

The stream could also be fast or slow depending on the situation, revealing how the marriage could be stagnating, exciting, or somewhere in-between. The stream could become a river that flows through the turbulence of rapids, the troubles, the fights, the struggles of a healthy marriage. Or it could flow as a waterfall, perhaps representing an affair or another type of severe betrayal.

But streams and rivers can also separate, bifurcating to different routes and locations. This bifurcation could represent a couple’s divorce, with each going their own way toward entirely separate lives.

There’s also a sense of irony in Williams diction and phrasing. The man and woman are different yet amalgamate as a stream. A stream suggests movement, but the poem is stuck in an eternal time loop, a single moment.

Now, I probably shouldn’t have extended the stream image to a river, especially as even streams have forks, rapids, and waterfalls. Marriage also represents a fleeting moment in time, thus extending an analysis further makes less sense. But my analysis is what the poem evoked in me, and it seems to comply with what Williams wrote. Somewhat.

You see, the “stream flow in a field,” and William’s preposition choice here adds much meaning. The stream is flowing “in” rather than through “a field.” How can a stream flow in a field? Surely it must end somewhere, in this case probably feeding the field. And this is why I suggested my river analogy detracts from the poem’s meaning. Marriage depicts a moment in time, a solitary and somewhat generic event. Therefore, it doesn’t matter that the stream “must end somewhere,” as I just said. It will end, but not in this moment, just as the marriage will one day end, in death or in divorce.

Marriage reminded me of Snow Patrol’s Chasing Cars:

These lyrics stood out most:

- “We’ll do it all / Everything / On our own,”

- “If I lay here / If I just lay here / Would you lie with me and just forget the world?”

- “Forget what we’re told / Before we get too old / Show me a garden that’s bursting into life”

The two people suggested in the poem, ambiguous like those in Marriage, are on the journey of life together. But one of them calls for a moment, “Would you lie with me and just forget the world?” to enjoy each other’s company and forget everything. That’s similar to how Williams places the couple from Marriage in a solitary moment with noting else described around them. That is apart from the field, like “a garden that’s bursting into life.” A fruiting, flowering, thriving garden requires water like that of a stream.

Despite the lack of time, this poem leads to a single conclusion that isn’t mentioned anywhere. People die. Obvious, I know. But this man and woman will one day die if they haven’t already. Their stream will stop one day. Maybe they divorced before that. Who knows? Marriage shows the future as undecided, the past as irrelevant. But it also reveals to us that moments of the present, whether big or small, ambiguous or detailed, really do matter, especially as those moments could end as quickly as it takes for you to read a momentous 14-line poem.