I first thought the funk rock song “Eminence Front” by rock band The Who was about putting on a different face depending on who you meet, your mood, the time of day, and so on. For instance, I act one way around my family, another way around my friends, and a different way around my teachers. I wanted to compare this idea to what we discussed in a Modern Poetry class about Baudelaire and the notion of how we have different personas for different situations. It turns out the parallels between “Eminence Front” and Baudelaire are stronger than I originally thought.

In researching this post I discovered that according to the band’s leader singer, Pete Townsend, “Eminence Front” refers to what happens when someone takes too much cocaine. The chorus even reveals this idea somewhat as Townsend sings “behind an eminence front” while the lead guitarist, Roger Daltrey, simultaneously sings “it’s an eminence front,” as if they’re somehow intoxicated and “seeing double” so to speak.

Clearly this overlap shows two different sides to the same person too. But the only sources I can find claiming the cocaine connection are Wikipedia that references an article no longer available online and a Quora reply. Urban Dictionary also has a similar idea about the connection between the song and cocaine.

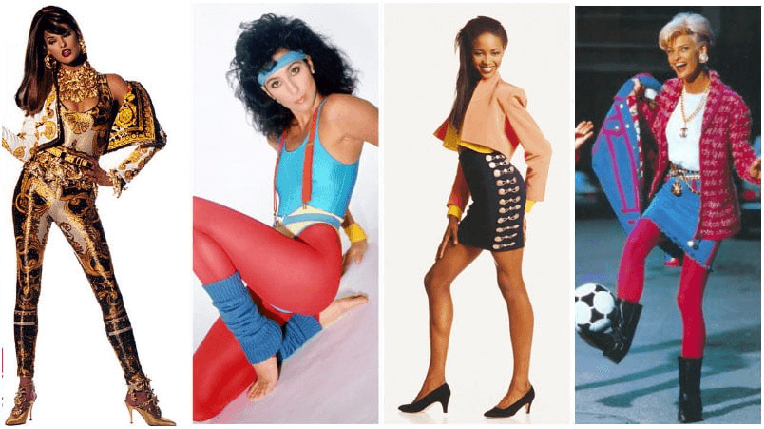

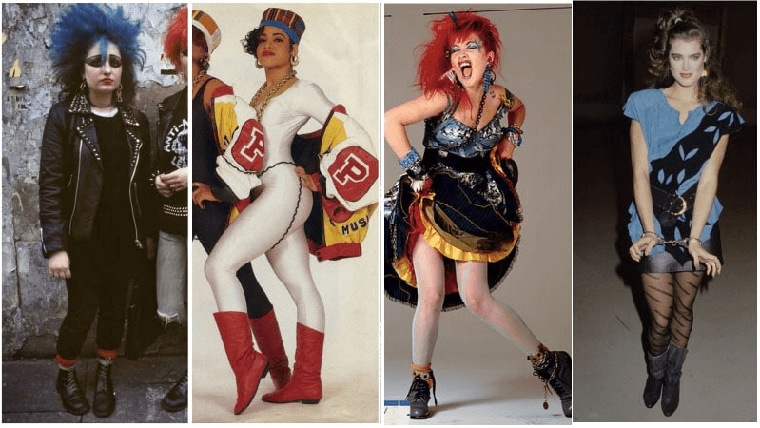

However, the idea makes sense because the song, published in 1982 also discusses the excesses of the period. The 1980s was known as “An Age of Excess” and opulence, meaning extreme wealth and glamour were at the fore of society. Everyone wanted to stand out, so even material objects needed to make bold statements. That meant objects like sunglasses were massive, shocking neon colors were the norm, and shiny materials like spandex and sparkly fabrics became common. Cocaine use was also high (no pun intended) and grew at a rapid rate.

1980s fashion

1980s fashion

Baudelaire described a kind of character, the dandy, in “The Painter of Modern Life” who aimed at being as individual as possible through the way he dressed and acted. Dandies remind me of people from the 1980s whose goal was to stand out by being different, by attracting attention in any way necessary.

The majority of the lyrics for “Eminence Front” focus on the following:

…

People forget

Forget they’re hiding

…

Behind an eminence front

Eminence front, it’s a put on

…

Come on join the party, dress to kill

…

Partial lyrics of “Eminence Front” by The Who

“Dress to kill” is likely a double entendre, referring to the idea of dressing to stand out or living a lifestyle that could lead to death that includes dressing excessively. “People forget…they’re hiding” because they’re either high or pretending to be someone they’re not, hence they’re putting on a front. There are also single phrases like “The drinks flow” and “That big wheel spins, the hair thins.” These phrases again focus on excess, that of alcohol and gambling.

So perhaps the best term for the 1980s is “hedonism.” This concept refers to the idea that one of the best goals a person can have is to pursue pleasure and self-indulgence. This concept reminded me of the modernist Decadent movement from about 100 years earlier. It was an artistic and literary movement that focused on excessive aesthetics and artificiality, but in conflict with hedonism. It was a response to the corruption of moral and cultural decay of the late 1800s rather than a promotion of it like that of hedonism.

But “Eminence Front” reminds me of the Decadent movement because the song is also against this moral and cultural decay. In fact, the last verse before the final chorus says: “The shares crash, hopes are dashed / People forget / Forget they’re hiding.” The Who is saying that the stock market might crash but people do not care. They’re hiding behind a false sense of reality, the “Eminence Front,” or being too high on cocaine to care or recognize what the drug is doing to them. Alternative “shares” could have a more social meaning too, in terms of shared experiences or shared realities. “Shares crash” could also refer to the withdrawal symptoms (“crash”) experienced after going off a drug like cocaine in which “hopes are dashed” and the reality that person was trying to avoid sets in again.

Also from the 1800s is Charles Baudelaire who, unlike the Decadent movement or The Who, promoted the idea of pleasure, especially drug usage. In 1850, he described the effects of hashish in striking detail in “The Poem of Hashish,” saying it is a form of “slow suicide” and “magic” that is unobjectionable and helps create the “artificial ideal.” Evidence suggests Baudelaire was describing opium, however.

Ten years later, in his book, “Les Paradis artificiels” (“Artifical Paradises”) Baudelaire discusses the effects of opium and hashish and suggests drugs could assist humans in achieving an idealized world. Like the “Eminence Front,” this state would create a false or “Artificial Paradise” that in some ways may be better for some people than having to deal with reality. More interestingly, it is said Baudelaire rarely indulged in drugs despite his reputation for debauchery. Either way, Baudelaire, known for his pursuit of pleasure through alcohol and sex, suffered from chronic alcoholism and the STD, tertiary syphilis.

The link between Baudelaire and “Eminence Front” can be further seen in Baudelaire’s prose poem, “The Eyes of the Poor.” The narrator is offended by the fact the woman he was with in a cafe appears to have no empathy for the poor father and his two children looking at them through the window.

Originally, I thought “the eyes of the poor” referred to those poor people who look on at the rich hoping but knowing they can never achieve such wealth. But after analyzing “Eminence Front,” and its idea that people put on fronts to hide their true nature, I now think differently. Perhaps the one with poor eyes is the lady who fails to see the divide between rich and poor and feel empathy toward them. Instead, she requests the narrator to “ask the maître d’ to send them away.” She also fails to see how the beauty and grandeur of antique art has been reduced to advertising gimmicks to attract the likes of her but also the narrator. Being a poem, this second meaning is perhaps obvious.

But the narrator who sees all of that also partakes in the cafe by visiting it when he has a choice not to do so, unlike the poor who have none. Yes, maybe the woman he was with would leave him, but he claims he will only be offended at her for a short time. So perhaps it is he who has the “eyes of the poor,” as he is able to see the injustice of poverty, to realize its implications, but would rather partake in enjoying the splendours of wealth than not. If he didn’t see poverty as a problem or feel “a little ashamed” that he could enjoy the cafe while the poor could not, his eyes would not be poor. He is also putting on an “eminence front” and covering it under the guise of being an observer. People “forget they’re hiding,” but do they really? Are they not just pretending they’re something else, playing dumb to avoid having to deal with the realities of the modern world whether in the 1880s or the 1980s or indeed the 2010s?

Art appears to encapsulate so much meaning from so many different periods that it proves the point that art reflects humanity. “Eminence Front” is music while Baudelaire’s writing and the Decadent movement are literature, but they all fall under the category of art. Their themes of drug usage, excess, moral decay, and pretending to hide the fact one recognizes reality seem as universal today as they did back then. One still has a choice to partake in it or to avoid it. But I think these three works of art suggest a third possibility, that we have the choice to do something about addressing the realities of the modern world, good or bad, whether for ourselves or for others.