I can’t find or think of a better example of the “show, don’t tell” technique than poetry’s imagism movement. I also think an explanation using images of a sculpture might help elaborate further on what it means compared to using just words.

What is Imagism?

In a Station of the Metro

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;

Petals on a wet, black bough.

Ezra Pound, In a Station of the Metro, an example of Imagism.

While this poem perhaps seems vague and ambiguous, at first, it is much more than that. Its simplicity and brevity evokes so much of your imagination that it does not need more words to explain it. Any more would ruin it. So much said with so few words. “Show, don’t tell” summarized then put on a diet. Next time you’re in a metro (or look at the picture above), take a look around at the faces you see and tell me Pound’s poem isn’t timeless!

The early 20th-century poetic movement, Imagism, was a reaction against poetry of the Romantic and Victorian eras. Poetry from these eras emphasize details, ornamentation, mystery, emotions, nature, and grandiose attempts at universal themes. The style also required strict structures, such as rhyme and meter.

Imagism reacted to that by emphasizing the idea of capturing a single moment in time, an exact image of a place or an event. That required simplicity, clarity, brevity, and extreme precision to create as much meaning as possible in as few words as possible. Instead of metaphors, imagism relied on “concrete images drawn in precise, colloquial language rather than traditional poetic diction and meter” (Poetry Foundation).

Ezra Pound revealed the idea in Poetry’s March 1913 issue, specifically A Few Don’ts. On a side note, do you see the probably intentional irony in his choice of the word “don’ts?” Pound define what he means by an “Image:”

An “Image” is that which presents an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time. I use the term “complex” rather in the technical sense employed by the newer psychologists, such as Hart, though we might not agree absolutely in our application.

…

It is better to present one Image in a lifetime than to produce voluminous works.

Ezra Pound, A Few Don’ts

His intention was to use an Image to evoke an extreme sense of emotion, or understanding, or realization, for example. Creating an Image required a few don’ts, including using “no superfluous word, no adjective which does not reveal something” and not use rigid rhythm or rhyme schemes.

The Imagists wrote succinct verse of dry clarity and hard outline in which an exact visual image made a total poetic statement.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, Imagist

Pound elaborates further in A Retrospect, published five years later in 1918. Along with poets Hilda Doolittle (“H. D.”) and Richard Aldington, Pound describes the three principles of imagism:

- Direct treatment of the “thing” whether subjective or objective.

- To use absolutely no word that does not contribute to the presentation.

- As regarding rhythm: to compose in the sequence of the musical phrase, not in sequence of a metronome.

Imagism Connected to Vorticist Sculpture

While imagism was a poetic movement, I’d like to explain imagism using images. And I have to use an interconnected movement from the art world, Vorticism, a term Pound coined (no pun unintentionally intended).

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica say, “Imagism sought analogy with sculpture,” as Pound promoted sculpture:

I would much rather that people would look at Brzeska’s sculpture and Lewis’s drawings, and that they would read Joyce, Jules Romains, Eliot, than that they should read what I have said of these men [certain French writers in The New Age in nineteen twelve or eleven], or that I should be asked to republish argumentative essays and reviews.

Ezra Pound, A Retrospect

Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound

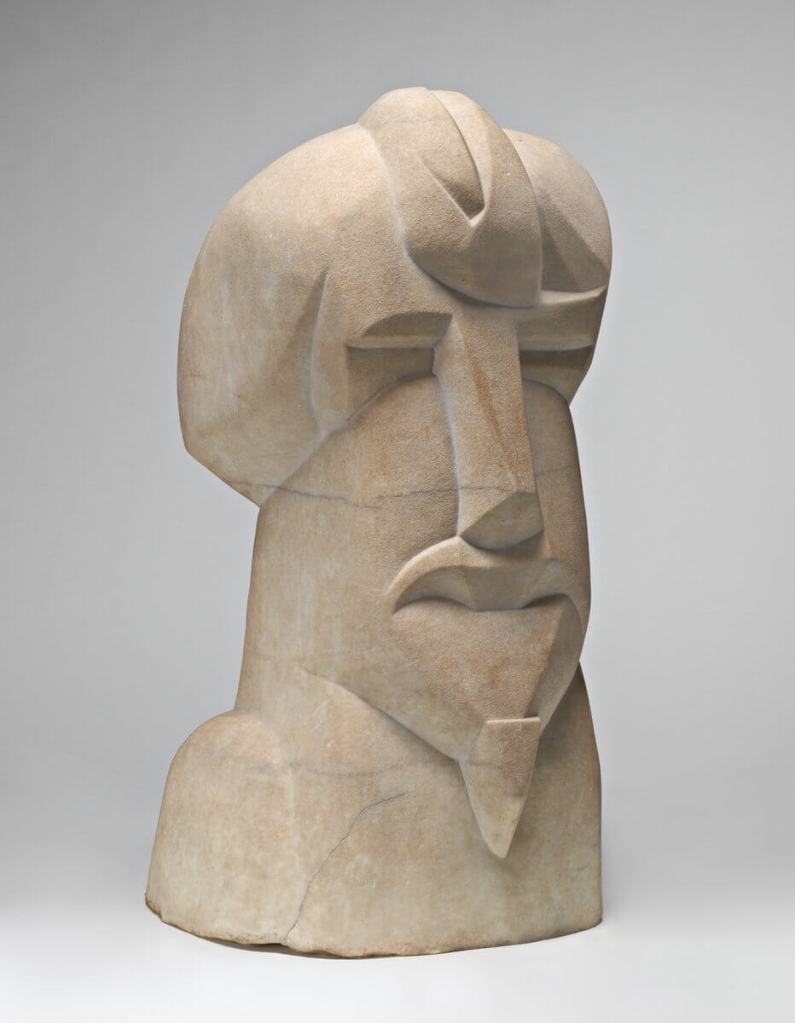

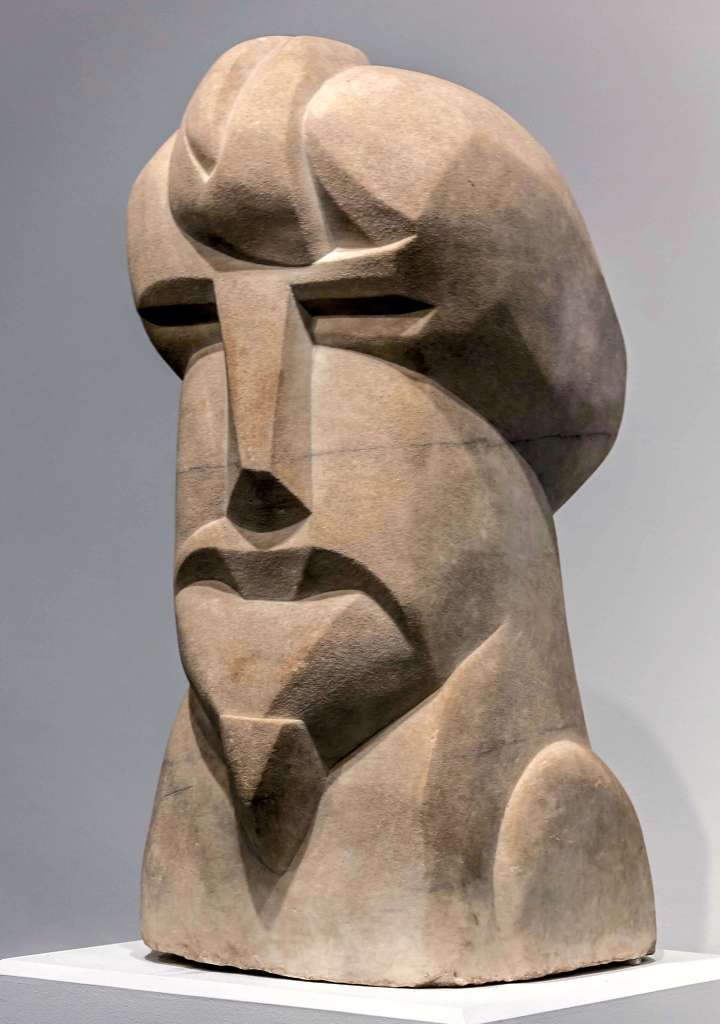

Pound refers to French painter and sculptor, Henry Gaudier-Brzeska’s, bust of himself, the Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound. He was 29 when he commissioned Gaudier-Brzeska to carve his bust, which he did by hand from stone.

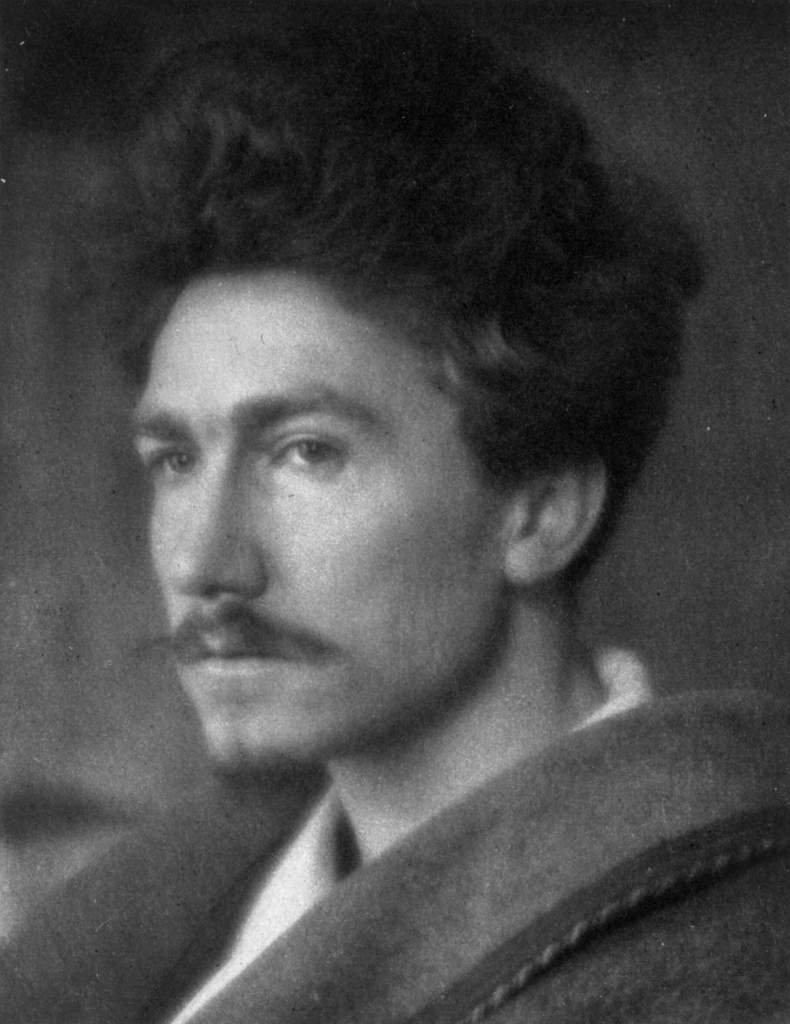

For comparison, here is a portrait photo of Pound age 28:

The bust captures the outline of Pound’s head with his larger forehead and pointier chin creating a triangular shape, as emphasized in the bust. You can also see his large hairdo and facial hair reflected in the sculpture.

However, the physical similarities end there. The bust appears surreal because it is somehow Pound and not Pound but still Pound. Let me explain! You can clearly see similarities between Pound’s physical head and the sculpted bust.

But the sculpture also captures Pound’s persona and personas, something intangible. The bust is human but not, it seems something more. You cannot tell whether he is old or young, you cannot tell what he is thinking, nor can you can understand what the sculptor’s intention was, at first glance.

The large hair, the direct and stern gaze, and the simple geometric lines suggest this person has power. He transcends normal humans to something more, to something god-like. The hair seems like a military helmet, again a depiction of power. After all, Pound was on a gargantuan mission to save poetry, something that required transcending regular human endeavour and ingenuity. Like imagism, this bust says so much about Pound with so little detail.

Imagism is the screenshot to vorticism’s single, short film scene or even a GIF. Imagism captures the exact moment of a scene in an almost timeless depiction of space. For example, the masses of people merging into one single mysterious blur of faces. Vorticism captures the actions of these people as they enter and exit the observers vision.

Imagism for the 21st Century

Pound looked to the past to help reshape and define the future of poetry. In Pound’s time, change often meant worsening situations and modernity meant people only recently experienced what it meant to have free time. Today, we seem to have less free time every day, and what little time we have needs to be optimized for brevity. Few people like to read anything more than the title of a news article or blog post, even less read longer social media posts. Imagism offers a solution. I mean, let’s not forget that “In a Station of The Metro” is the title but also part of the text. How about that for brevity?

Imagism takes the “show, don’t tell” technique to the extreme. It seems like a small part of an image captured in words, yet it inspires your imagination to picture that image in a way few other literary movements can claim to achieve. Saying more with so few words like imagism prescribes seems better than saying less with more words. This idea seems more important than ever in today’s world of fast and not so fastidious information.

Photo by Eddi Aguirre on Unsplash

Pingback: The Intricacies of Marriage in Just 14 Words | Niall's Modern Poetry Blog